Aja Edwin Mujinga | ART

(aka. Aja Mujinga Sherrard)

, is repair

This performance installation featured over three hundred handmade ceramic plates shaped to resemble notebook pages, which were installed in two grids on either side of a freestanding, perpetually running sink. Across the first grid, each plate was inscribed with handwritten text featuring some fragment of a narrative dealing with loss, anxiety, fear, shame, or some other emotional burden. These were a mix of my personal writing and a number of other writings contributed anonymously by members of the local community over the course of several preliminary events. Displayed together, the variety of handwritings, writing styles, and even the occasional variance of language created an interesting effect: the abundance of voices transformed each individual incident of raw vulnerability into a collective act of openness.

For the duration of the exhibit, I performed the piece by washing the inscribed plates clean for an hour each day that the gallery was open. As I performed, the second grid filled with these washed ceramic pages. Visitors were encouraged to take these from the wall and write their contributions on them at an adjacent table, before replacing them in the inscribed grid. This allowed the piece to inhabit the gallery as a living project, and to signal the open cycle of healing and loss.

, is repair originated very simply as a narrative piece, telling the story of a year in mourning after the death of my father, when I found myself compulsively doing dishes. This mundane, emotionally and intellectually silent gesture enabled me to perform a small act of repair: returning a messy, dysfunctional object to a state of wholeness, resolution, and readiness. Washing became a private, insular act of healing by metaphor when the actual dysfunction of grief seemed insurmountable. Over the course of the year, however, I discovered that self-repair has the potential to be expansive, and this compulsive, private act created space for healing beyond my own.

This piece was exhibited and performed at the Gallery of Visual Arts at the University of Montana in 2016 and again at the UC Gallery in Missoula in 2017.

Photos by Sarah Moore

Press: Missoulian, Montana Kaimin

Them/me

This project was conceived and completed in collaboration with Crista Ann Ames (link)

Owing a lot to privilege inventories like the seminal essay Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack by Peggy McIntosh, this exhibit’s engagement with the vocabulary of privileges was a reaction to the brittle and anxious psychological landscape of the post-election. Living in a small city in the midst of a vast red state—one which had overwhelmingly supported a sexual predator for office and the white-supremacist, anti-immigrant, homophobic, and ableist ideologies associated with him—it seemed impossible to avoid the heightened sense of being visible for all those traits that could so easily draw hatred or violence from the people around us. This produced a kind of longing for some form of invisibility, or psychological safe passage, while simultaneously throwing into sharp relief the ways in which we were each already masked within certain privileges or apparent privileges. In this heightened landscape, the ways in which we seemed safe (For Ames, the lack of visual traces from certain experiences that amplified her sense of vulnerability as a woman; for Sherrard, the light skin that masked her African heritage, the gender presentation that masked her queerness, and the education and accent that masked her history as an immigrant) became almost as heavy and frightening as the ways in which we weren’t.

This collaborative exhibit draws from Ames’ background in figurative ceramic sculpture, Sherrard’s background in conceptual art, and both of their experimentations with textile work in order to reimagine this vocabulary of privileges as an ominous crowd of spectral figures or mask-shrouds. Each can be lifted from the wall and donned over the viewer’s faces, temporarily rendering our individual selves invisible and affording us a moment of release from identity hyper-vigilance. A notebook inscribed with the phrase, “If I were ___ I would” invites us to reflect on and record that moment of ‘freedom’.

Beneath each mask is another level of imagery: a series of figurative hands, diversified by clay bodies and coloration and far more corporal and human than the abstracted identities they support. Each hand forms a gesture that speakers of American Sign Language may recognize: seen together, the hands spell out an echo of that phrase, “If I were I would” and in so doing, affirm the vulnerable and very human quality of such a sentiment. Perhaps, then, we might empathize with such a longing—even, and especially, our own.

But not without limits.

There are two books, equal in size and color, positioned on either side of the gallery—and while one of them offers us the opportunity to explore the absence of such privileges from our lives and how those absences may leave us vulnerable, or longing, the second book is inscribed with just one privilege; the final thing we may long for when in possession of these others: “freedom from accountability.” That book does not open.

Frightened and weary as we may be, we cannot escape our complicity in creating this crowd of ghosts. We must stand before them, and we must see them.

This piece was installed in the Jodee Harris Gallery at Seton Hill University, PA in 2018, in conjunction with the NCECA ceramics conference.

to whom it may concern

This project was conceived and completed in collaboration with Crista Ann Ames (link)

_________________________________________________

To whom it may concern:

#Metoo, #Blacklivesmatter, Water Protectors, “Water Is Life,” Pride, #Yesallwomen, #Takeaknee, “The Future Is Female,” “Time’s Up,” “People Before Profit,” “No One Is Illegal,” “Native Lives Matter,” “Disabled Lives Matter,” “Hands Up Don’t Shoot,” “Refugees Welcome,” “Coexist,” “Silence = Death,” “We Can Do It,” “Stand With Standing Rock,” “Not Gay As In Happy: Queer As In F*Ck You,” “Stop Global Warming,” “There Is No Planet B,” #whyIstayed, “Love Wins,” “Justice For Palestine,” “Say Her Name,” “Resist,” “Water Is Life,” “Protect Kids, Not Guns,” “Enough”, “Never Again,” “Save Our Winters,” #Bringbackourgirls, “Actions Not Prayers,” “Love Makes A Family,” “Books Not Guns,” “Love Is Love,” “And Yet, She Persisted,” “Disabled And Proud,” “The Future Is Accessible,” “Piss On Pity,” “System Change, Not Climate Change,” “One Earth, One Chance,” “Science Not Silence,” “Build Bridges, Not Walls,” “Power to the People” “Hope,” . . .

These are our words

And they have also become our things.

T-shirts, hats, stickers, flags, wristbands, posters, fliers, buttons, tote bags, banners . . .

whether mass-produced or hand-knitted/ painted/ printed . . .

what becomes of them?

Do they pile up? Dust over?

Do they fill trash cans and landfills?

Do they lose meaning as they amass, becoming only noise? Only stuff?

Or, perhaps, do they linger, dormant?

Can we imagine them as seeds to a legacy?

_________________________________________________

In this collaborative exhibition, Crista Ann Ames and I explore this last possibility. By housing the material detritus of contemporary activism in seed pods made of ceramic—evoking the qualities of timelessness and decay inherent to “earth”—we visualize the most hopeful telling of a complex story about values, activism, identity, liberalism, and consumerism.

This piece was installed at “The General Public” Garmentory/Gallery in Missoula, MT, for the September First Friday Art-walk in 2019.

Ballot Project

This project was conceived and completed in collaboration with Crista Ann Ames (link)

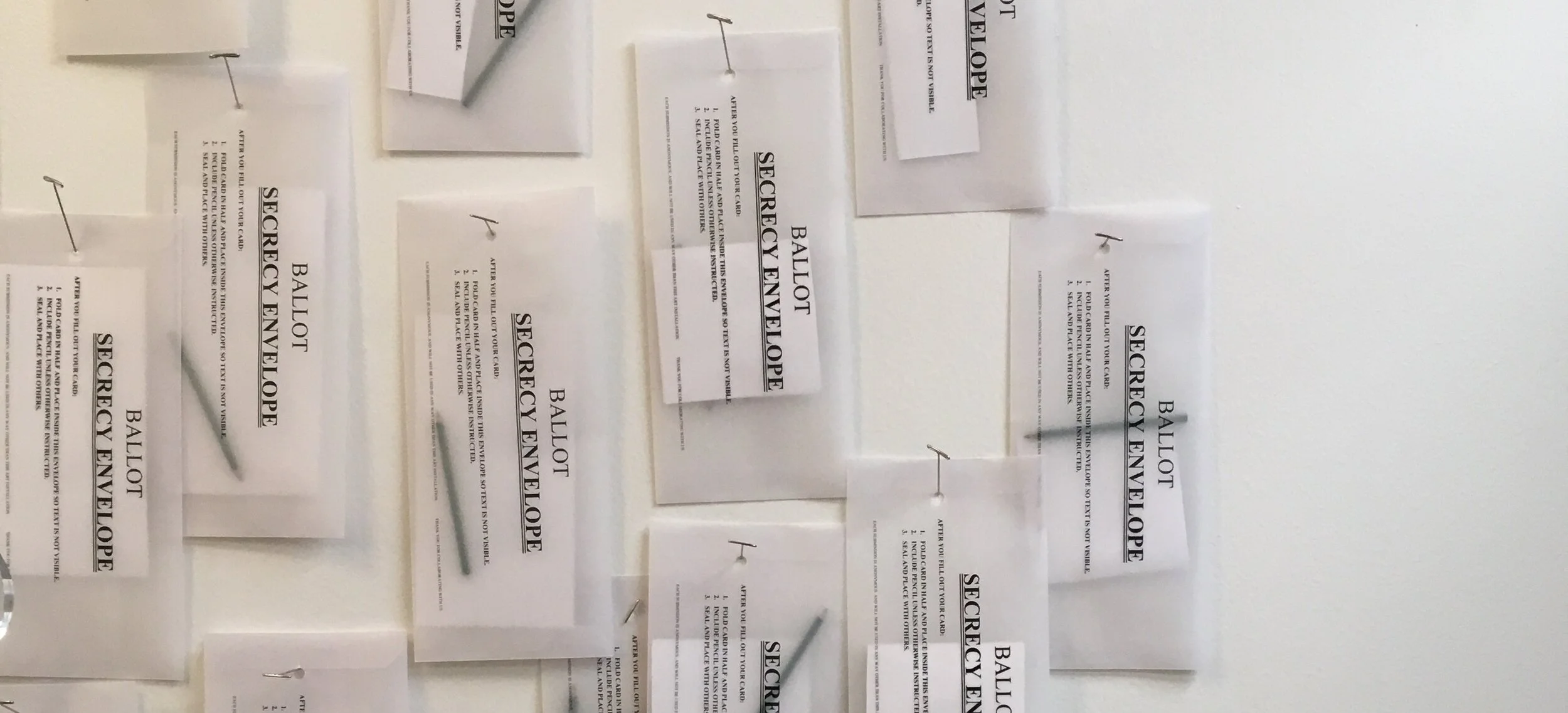

The small green pencils featured in this project are a found material: surplus absentee pencils originally intended to be included in mail-in ballots but ultimately abandoned to a thrift store in the Red Lodge, MT area. As another election season draws closer and larger in our thoughts, we found that the pencils had taken on a potent metaphoric property. Presenting the single-use pencils to our audience as single opportunities to speak within the electoral process, we offered our audience a chance to consider how and when we use our political voices. The presidential election only? The presidential and Midterm elections? Every election, including all state and local elections? Not voting at all?

Installed alongside the project to whom it may concern , the inherent irony of a translucent secrecy envelope certainly addresses the way in which voting—or not voting—can be wrapped up in identity and virtue/values signaling despite its core premise of privacy. Though the installation of the envelopes allows for the content of each ‘Ballot’ to remain hidden, each envelope does reveal something. For the selection “I don’t vote,” we invited participants to keep the absentee pencil as their own—hopefully to express themselves in some other way.

Accepted and hung anonymously, we treated these envelopes a sculptural medium whose collective body might inspire meaningful reflection—and action.

This piece was installed at “The General Public” Garmentory/Gallery in Missoula, MT, for the September First Friday Art-walk in 2019.

Costuming Kinship

Currently comprising of three photographs: Costuming Ethnic: The Artist and her Mother, Costuming Ethnic: The Artist and her Father , , and Costuming Ethnic: The Artist and her Grandmother , the Costuming Kinship project interrogates the coherence of race by performing the extent to which race fails to coherently apply within my own multiracial bloodline.

In each photograph, I posed beside a member of my family to whom I am related by blood while wearing acrylic paint and crude costume elements such as a wig, blazer, or dark contacts in order to appear to be the same race as they are. The conceptual parameters of the project dictated that I must be painted in person with acrylic paint, not digitally altered, and that the family member I was costuming had to be present for the entirety of the shoot. These parameters are purposeful: acrylic paint, with its plastic sheen and masklike quality, emphasize the disconcerting, artificial quality of the images, while the act of sealing my face and neck within this plastic ‘false skin’ embedded a quality of physical discomfort. Requiring that my family members witness and participate in the physical experience emphasized an emotional or psychological discomfort as well, illustrating the strain that such ‘corrective’ acts of identification created within our actual relationships. In the photographs where I costume darker than my natural skin tone, chilling echoes of blackface and the violent racial history of caricature, degradation, and appropriation from the era of American Minstrelsy on through contemporary hate crimes and racist parodies imbue the project with a third level of social and historical discomfort.

In short, the images are disturbing: they are eerily false, and politically wrong—even though they propose to be more “true” according to social constructions of race and family in the United States than the reality of our bodies could be. In this project, I am treating my body and experiences as a site of incoherence or rupture within those constructions. Calling the system of race into question, the work asks: “How can this be true while I am true?”

This piece was installed in a group exhibition at the Gallery of Visual Arts in Missoula, MT in 2014.

Photos by Liliane Evers, and Beth Korth

Lettres pour Yaya Mujinga, as read by her grandchild

The loss of my maternal grandmother significantly changed the landscape of my family. With her death, our generation lost its footing in the complex territory of cultural identity and memory. Among her fifteen grandchildren, I was fortunate to be the only one who ever traveled to the Democratic Republic of the Congo with her and who was able to meet the extended family she had been forced to leave behind. It was perhaps for this reason that I was the one to inherit the stack of letters featured in the performance piece: Lettres Pour Yaya Mujinga, as read by her grandchild. The letters were one half of a correspondence dating back approximately fifty years between Mujinga and her uncles, brothers, sisters, cousins, and their children. The majority of them were written in my grandmother’s natal language of Tshiluba, which I can neither speak nor understand.

Performing Lettres Pour Yaya Mujinga, I addressed these letters as a representation of both the loss of my grandmother and the parallel loss of language, history, and belonging that our colonized relationship represented. Placing myself at a small table in an anonymous parking lot, I read the letters aloud for a period of eight hours. This was an act of mourning, reverence, and closure. Yet, the fractured strain in my voice as I stumbled through handwritten Tshiluba with uncertainty and increasing exhaustion also signaled the void left by her death, my distance, and our colonial displacement.

This piece was performed for eight hours in a public parking lot in Missoula, Montana on October, 23, 2015.

The desk and letters were also installed with an eight-hour audio recording of the reading at the Gallery of Visual Arts in 2016.

(Our) Baby Blanket

(Our) Baby Blanket reflects the challenge of mourning two people at once. It addresses irreconcilable histories conjoined by loss; the anxiety that one is better mourned than the other; and the inevitability of their juncture, however unharmonious, in the tender and intimate body of the quilt.

For the piece, I recovered a quilt both my father and I had been wrapped in as infants. The hand-made, fifty-year old blanket was badly torn and in a state of disrepair. Treating this shared heirloom as a representation of my paternal history, I sought to articulate my complicated role in his family through an act of corruptive repair. Although the quilt featured a simple design in pale green and soft floral print, I repaired it with bold and sturdy wax cloth, or pagne, inherited from my Congolese Grandmother. In addition to associating the fabric to her and to the African character of my maternal family, I also considered it an autobiographical symbol: like myself, the wax cloth is a global hybrid with a complex colonial lineage. Through the disruptive insertion of this cloth into the original pattern, our blanket was both repaired and not repaired. The pattern was destroyed by my contribution, the new fabrics glaring from the docile green material, and the tattered shreds were still visible beneath my timid stitches.

This piece was installed as part of the Solo Exhibition, “Dissonate,” at FrontierSpace Gallery in Missoula in 2015, and again at the Gallery of Visual Arts in 2016.

Me: Your Daughter, Him: Your Miller

Me: Your Daughter, Him: Your Miller deals with the persistence of interpersonal wounds after a death and the way societal violence—such as misogyny—may interrupt our relationships and hinder the process of mourning.

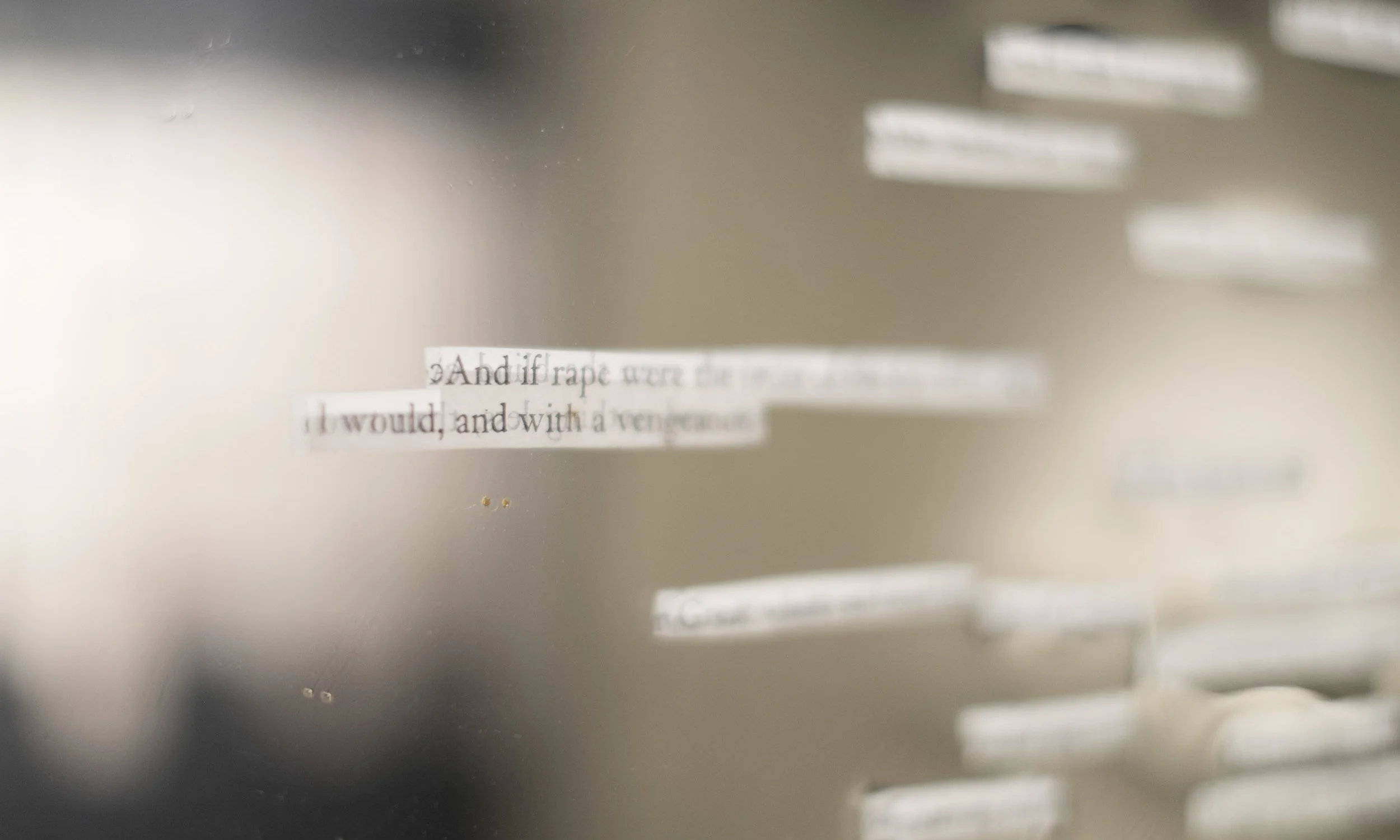

In the year following my father’s death, I mourned him in part by retracing his steps through the literature he had loved while he was alive. This brought me to Henry Miller’s autobiographical novel: Tropic of Cancer. In journals from my father’s mid twenties, he describes himself as a nearly fanatical admirer of Miller—the journals from the period emulate Miller’s wit and Miller’s language. Though I knew enough to anticipate some misogyny, some racism, and some expatriate arrogance, what I encountered in the text was intolerable. The resulting question was compulsive: How can someone have idolized this language and also have, or love, an adult multiracial daughter?

In the creation of Me: Your Daughter, Him: Your Miller, I consolidated the effect of Henry Miller’s misogynistic language by cutting every incident of the word “cunt,” “bitch,” “whore,” “wench,” or concisely misogynistic phrases, such as “…if rape is the order of the day, then rape I will, and with a vengeance..” or, “…You can pinch her ass if you like...” from Tropic of Cancer. These were interspersed with handwritten cuttings of similar phrases from a journal my father had kept in his mid-twenties. The total collection of misogynistic clippings was then resin-cast over the reflective surface of a full-length mirror that had been a gift from my father to myself.

This piece was installed at the Gallery of Visual Arts in Missoula, MT in 2016

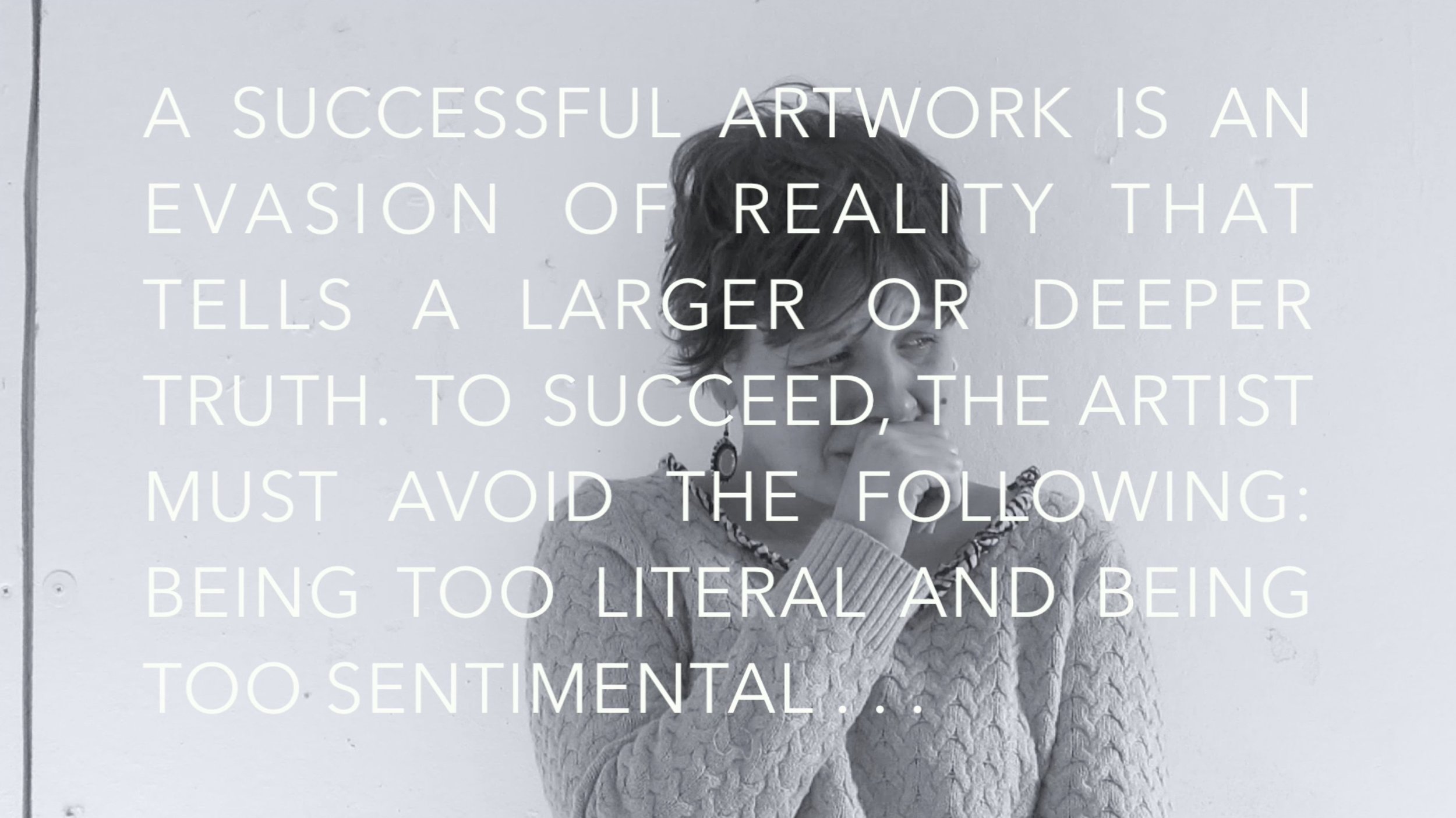

"A Successful Artwork"

This project features a fifteen-minute, single-take silent film of myself crying beneath a static phrase reading the following: “a successful artwork is an evasion of reality that tells a larger or deeper truth. to succeed, the artist must avoid the following: being too literal and being too sentimental.” The phrase was taken from a conversation with poet, Prageeta Sharma, on the subject of art and sincerity.

By pairing this expression of raw, unchecked emotion with the censoring veil of critical language, the piece articulated a central issue emerging in this moment of my practice: how might I continue to make intelligent work while grieving a sudden and difficult death?

This piece was installed on informational screens throughout the Fine Arts Building at University of Montana in 2015, and again as part of the Solo Exhibition, “Dissonate,” at FrontierSpace Gallery in Missoula in 2015.

Body Double

The piece, Body Double, explored the possibility of creating a sensation of incoherence through an overabundance of conflicting information. The piece consisted of 365 copies of my birth certificate, each of which were individually falsified with the adjustment of some significant or insignificant details: alternate names my parents may have considered, the insertion of a step-parent in the place of a biological one, an alternate home address, alternate birthing attendant, and so forth. Displayed in a wall-to-wall grid, the potential realities are expansive and seemingly endless. The single ‘true’ birth certificate among them is neither removed nor erased, but rendered meaningless.

The piece points to records and paper trails as supposed confirmations of stable identities and proposed that these, too, have a fragile role in the support of coherent public identities. It references long histories of falsified or erased documentation as a tool of social manipulation across the globe and it protests the cold and unyielding summary a person into the form of documents. Additionally, the piece is an act of nostalgia—visualizing the disorienting consequences of engaging the proposition, “what if…?”

This piece was installed as part of the Solo Exhibition, “Dissonate,” at FrontierSpace Gallery in Missoula in 2015.

Which Is and Isn't Mine

Which Is and Isn’t Mine is a thirty-minute single-take performance video projected of over the surface of a text painting.

The performance involves myself painting the portrait of a black woman over top of my face in acrylic paint, followed by the portrait of a white woman over the first, before I finally peel the acrylic from my face in skin-like shreds. This video is then projected over a neurotically condensed screen of language and pattern expressing the intellectual and emotional tension between multiracial anxiety, longing for ‘racial visibility’, and the violent history of blackface imagery in the united states.

This piece was installed as part of a group exhibition at the FrontierSpace Gallery in Missoula, MT in 2013

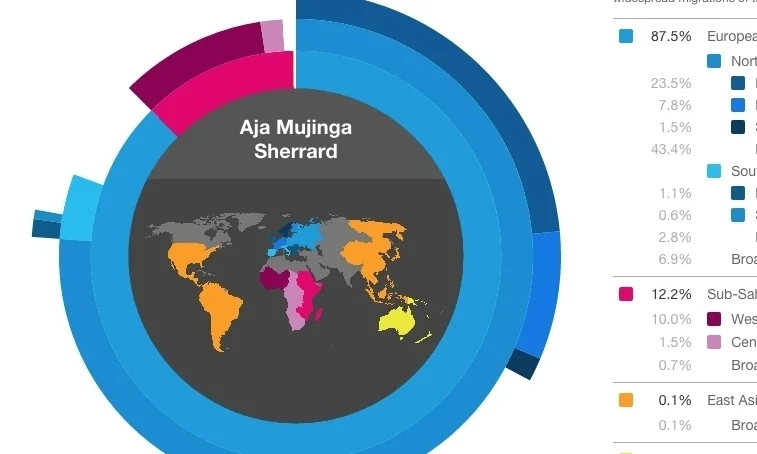

13 ≠ 12 ≠ 12.2 (Genetics Project)

As a field rooted in objective observations of the concrete universe, Science, and scientific discourse, implies a certain authority over what is “real.” The terms employed by scientific discourse are largely understood as fixed and coherent elements of reality around which subjective experiences may navigate.

Although the lived experience of Race and racial identity formation is often complex: nuanced, subjective, and even self-contradictory, Race itself is generally regarded as a stable concept. Terms such as “Black/African American,” “White/Non-Hispanic” and “Hispanic/Latino” are primarily accepted as fixed terms with definable qualities and boundaries—real and valid means of describing ourselves and others.

I believe that our cultural investment in Race as “true” is mirrored by, and to some extent grounded in, the use of Race and racial categorization within scientific projects and language. Genealogy projects such as The Geno-Graphic project sponsored by National Geographic and the business of racial identification via DNA testing exampled by programs such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe reinforce our cultural understanding of race as objectively real.

By sending my own genetic material to the three primary DNA testing labs in the US: National Geographic, Ancestry.com, and 23andME, I have subjected myself and my own racial identity to authoritative analysis. The subtle inaccuracies or inconsistencies between these results, I submit as a as an interrogation of that “real.”